Living History in the Classroom

News

SUMMARY: For three weeks of the semester, Alison Sandman transforms her Wilson Hall classroom into a nineteenth-century English town: part town hall, part marketplace, part public house. Students become part of an exercise in living history, turning a typical history class into an invigorating and unforgettable experience.

For three weeks of the semester, Alison Sandman transforms her Wilson Hall classroom into a nineteenth-century English town: part town hall, part marketplace, part public house. Populated with factory owners and workers, aristocrats and spinsters — many played by students studying to be teachers — the town is a simulation exercise that explores how history, geography and economics intersect.

To prepare, Sandman's students in HIST 333: Maps, Money, Manufacturing and Trade read deeply about Industrial Revolution-era Britain and study primary source texts, including posters and propaganda, to understand their characters’ concerns and motivations.

As part of the game “Rage Against the Machine: Technology, Rebellion, and the Industrial Revolution,” Sandman provides students with character biographies and parameters, such as cotton prices or social expectations, but no other requirements or script. The magistrate must favor law and order, for example, but the student decides how that viewpoint influences action.

As part of the game “Rage Against the Machine: Technology, Rebellion, and the Industrial Revolution,” Sandman provides students with character biographies and parameters, such as cotton prices or social expectations, but no other requirements or script. The magistrate must favor law and order, for example, but the student decides how that viewpoint influences action.

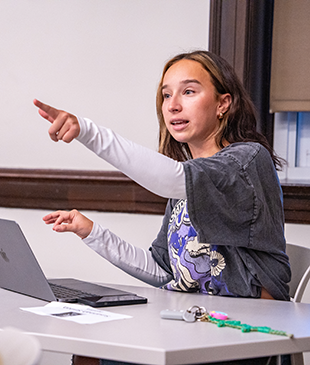

In this microcosm, students vie for prestige and a chance to be heard. During the “open, free-for-all” simulation, students acting entirely in character debate the merits of trade and voting rights, donate to charitable causes and strike economic deals. Reform-seeking workers organize or protest. Factory owners facing a labor shortage bid up the price of labor or hire immigrants.

Afterward, the class debriefs with guided reflection: How did they end up with a high-wage equilibrium? Why was it harder to recruit angry workers? What makes revolution less likely? Then, they apply what they learned to the present. The exercise guides students to associate intellectual work with lived experience. As Sandman explains, “Simulations help them see connections they would not otherwise see, and it helps them feel power relations in a way that analyzing them can’t.”

This simulation-reflection model comes from the Reacting to the Past games developed by The Reacting Consortium at Barnard College, a group of humanities, sciences and social sciences scholars. Sandman learned about the program from history colleague Rebecca Brannon, who recognized its potential for “unleashing our students’ drive into a new way to learn.” Brannon secured funding from the JMU President’s office to travel with Sandman to Athens, Georgia, to learn about game methods and administration, and they have shared the lessons with other JMU faculty.

This simulation-reflection model comes from the Reacting to the Past games developed by The Reacting Consortium at Barnard College, a group of humanities, sciences and social sciences scholars. Sandman learned about the program from history colleague Rebecca Brannon, who recognized its potential for “unleashing our students’ drive into a new way to learn.” Brannon secured funding from the JMU President’s office to travel with Sandman to Athens, Georgia, to learn about game methods and administration, and they have shared the lessons with other JMU faculty.

Brannon has run the “Patriots, Loyalists, and Revolution in New York City, 1775-1776” game in her early American history course several times. Students move quickly from skeptical to passionate about the experience, she says, and are “taken in by the buzz in the classroom from the moment the game simulation begins.” Sandman’s students say the exercise helps them experience the relationship between economics and politics; one said she now understands why workers thought breaking machines was their only recourse. Simulations aren’t the typical classroom experience, but they turn a history class into an exercise in living history.